Screen-printing

| Part of the series on the History of printing |

||

| Woodblock printing | 200 | |

| Movable type | 1040 | |

| Printing press | 1454 | |

| Lithography | 1796 | |

| Laser printing | 1969 | |

| Thermal printing | circa 1972 | |

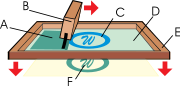

Screen printing is a printing technique that uses a woven mesh to support an ink-blocking stencil. The attached stencil forms open areas of mesh that transfer ink as a sharp-edged image onto a substrate. A roller or squeegee is moved across the screen stencil, forcing or pumping ink past the threads of the woven mesh in the open areas.

Screen printing is also a stencil method of print making in which a design is imposed on a screen of silk or other fine mesh, with blank areas coated with an impermeable substance, and ink is forced through the mesh onto the printing surface. It is also known as Screen Printing, silkscreen, seriography, and serigraph.

Contents |

Etymology

There is considerable etymological and semantic discussion about the process, and the various terms for what is essentially the same technique. Much of the current confusion is based on the popular traditional reference to the process of screen printing as silkscreen printing. Traditionally silk was used for screen-printing, hence the name silk screening. Currently, synthetic threads are commonly used in the screen printing process. The most popular mesh in general use is made of polyester. There are special-use mesh materials of nylon and stainless steel available to the screen printer.

Encyclopedia references, encyclopedias and trade publications also use an array of spellings for this process with the two most often encountered English spellings as, screenprinting spelled as a single undivided word, and the more popular two word title of screen printing without hyphenation.[1][2][3]

History

Screen printing first appeared in a recognizable form in China during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 AD).[4][5] Japan and other Asian countries adopted this method of printing and advanced the craft using it in conjunction with block printing and hand applied paints.

Screen printing was largely introduced to Western Europe from Asia sometime in the late 1700s, but did not gain large acceptance or use in Europe until silk mesh was more available for trade from the east and a profitable outlet for the medium discovered.

Screen printing was first patented in England by Samuel Simon in 1907.[5][6] It was originally used as a popular method to print expensive wall paper, printed on linen, silk, and other fine fabrics. Western screen printers developed reclusive, defensive and exclusionary business policies intended to keep secret their workshops' knowledge and techniques.[7]

Early in the 1910s, several printers experimenting with photo-reactive chemicals used the well-known actinic light activated cross linking or hardening traits of potassium, sodium or ammonium Chromate and dichromate chemicals with glues and gelatin compounds. Roy Beck, Charles Peter and Edward Owens studied and experimented with chromic acid salt sensitized emulsions for photo-reactive stencils. This trio of developers would prove to revolutionize the commercial screen printing industry by introducing photo-imaged stencils to the industry, though the acceptance of this method would take many years. Commercial screen printing now uses sensitizers far safer and less toxic than bichromates. Currently there are large selections of pre-sensitized and "user mixed" sensitized emulsion chemicals for creating photo-reactive stencils.[7]

Joseph Ulano founded the industry chemical supplier Ulano and in 1928 created a method of applying a lacquer soluble stencil material to a removable base. This stencil material was cut into shapes, the print areas removed and the remaining material adhered to mesh to create a sharp edged screen stencil.[8]

Originally a profitable industrial technology, screen printing was eventually adopted by artists as an expressive and conveniently repeatable medium for duplication well before the 1900s. It is currently popular both in fine arts and in commercial printing, where it is commonly used to print images on Posters, T-shirts, hats, CDs, DVDs, ceramics, glass, polyethylene, polypropylene, paper, metals, and wood.

A group of artists who later formed the National Serigraphic Society coined the word Serigraphy in the 1930s to differentiate the artistic application of screen printing from the industrial use of the process.[9] "Serigraphy" is a combination word from the Latin word "Seri" (silk) and the Greek word "graphein" (to write or draw).[10]

The Printer's National Environmental Assistance Center says "Screenprinting is arguably the most versatile of all printing processes."[11] Since rudimentary screenprinting materials are so affordable and readily available, it has been used frequently in underground settings and subcultures, and the non-professional look of such DIY culture screenprints have become a significant cultural aesthetic seen on movie posters, record album covers, flyers, shirts, commercial fonts in advertising, in artwork and elsewhere.

History 1960s to present

Credit is generally given to the artist Andy Warhol for popularizing screen printing identified as serigraphy, in the United States. Warhol is particularly identified with his 1962 depiction of actress Marilyn Monroe screen printed in garish colours.[12][13]

American entrepreneur, artist and inventor Michael Vasilantone would start to use, develop, and sell a rotary multicolour garment screen printing machine in 1960. Vasilantone would later file for patent[14] on his invention in 1967 granted number 3,427,964 on February 18, 1969.[15] The original rotary machine was manufactured to print logos and team information on bowling garments but soon directed to the new fad of printing on t-shirts. The Vasilantone patent was licensed by multiple manufacturers, the resulting production and boom in printed t-shirts made the rotary garment screen printing machine the most popular device for screen printing in the industry. Screen printing on garments currently accounts for over half of the screen printing activity in the United States.[16]

In June of 1986, Marc Tartaglia, Marc Tartaglia Jr. and Michael Tartaglia created a silk screening device which is defined in its US Patent Document as, "Multi-colored designs are applied on a plurality of textile fabric or sheet materials with a silk screen printer having seven platens arranged in two horizontal rows below a longitudinal heater which is movable across either row." This invention received the patent number 4,671,174 on June 9, 1987, however the patent no longer exists. This invention is still used today in the family owned silk screen business National Sportwear in Belleville, New Jersey.

Graphic screenprinting is widely used today to create many mass or large batch produced graphics, such as posters or display stands. Full colour prints can be created by printing in CMYK (cyan, magenta, yellow and black ('key')). Screenprinting is often preferred over other processes such as dye sublimation or inkjet printing because of its low cost and ability to print on many types of media.

Screen printing lends itself well to printing on canvas. Andy Warhol, Rob Ryan, Blexbolex, Arthur Okamura, Robert Rauschenberg, Harry Gottlieb, and many other artists have used screen printing as an expression of creativity and artistic vision.

Printing technique

A screen is made of a piece of porous, finely woven fabric called mesh stretched over a frame of aluminium or wood. Originally human hair then silk was woven into screen mesh; currently most mesh is made of man-made materials such as steel, nylon, and polyester. Areas of the screen are blocked off with a non-permeable material to form a stencil, which is a negative of the image to be printed; that is, the open spaces are where the ink will appear.

The screen is placed atop a substrate such as paper or fabric. Ink is placed on top of the screen, and a fill bar (also known as a floodbar) is used to fill the mesh openings with ink. The operator begins with the fill bar at the rear of the screen and behind a reservoir of ink. The operator lifts the screen to prevent contact with the substrate and then using a slight amount of downward force pulls the fill bar to the front of the screen. This effectively fills the mesh openings with ink and moves the ink reservoir to the front of the screen. The operator then uses a squeegee (rubber blade) to move the mesh down to the substrate and pushes the squeegee to the rear of the screen. The ink that is in the mesh opening is pumped or squeezed by capillary action to the substrate in a controlled and prescribed amount, i.e. the wet ink deposit is proportional to the thickness of the mesh and or stencil. As the squeegee moves toward the rear of the screen the tension of the mesh pulls the mesh up away from the substrate (called snap-off) leaving the ink upon the substrate surface.

There are three common types of screenprinting presses. The 'flat-bed', 'cylinder', and the most widely used type, the 'rotary'.[11]

Textile items printed with multi-colour designs often use a wet on wet technique, or colors dried while on the press, while graphic items are allowed to dry between colours that are then printed with another screen and often in a different color after the product is re-aligned on the press.

The screen can be re-used after cleaning. However if the design is no longer needed, then the screen can be "reclaimed", that is cleared of all emulsion and used again. The reclaiming process involves removing the ink from the screen then spraying on stencil remover to remove all emulsion. Stencil removers come in the form of liquids, gels, or powders. The powdered types have to be mixed with water before use, and so can be considered to belong to the liquid category. After applying the stencil remover the emulsion must be washed out using a pressure washer.

Most screens are ready for recoating at this stage, but sometimes screens will have to undergo a further step in the reclaiming process called dehazing. This additional step removes haze or "ghost images" left behind in the screen once the emulsion has been removed. Ghost images tend to faintly outline the open areas of previous stencils, hence the name. They are the result of ink residue trapped in the mesh, often in the knuckles of the mesh, those points where threads cross.[17]

While the public thinks of garments in conjunction with screenprinting, the technique is used on tens of thousands of items, decals, clock and watch faces, balloons and many more products. The technique has even been adapted for more advanced uses, such as laying down conductors and resistors in multi-layer circuits using thin ceramic layers as the substrate.

Stenciling techniques

There are several ways to create a stencil for screenprinting. An early method was to create it by hand in the desired shape, either by cutting the design from a non-porous material and attaching it to the bottom of the screen, or by painting a negative image directly on the screen with a filler material which became impermeable when it dried. For a more painterly technique, the artist would choose to paint the image with drawing fluid, wait for the image to dry, and then coat the entire screen with screen filler. After the filler had dried, water was used to spray out the screen, and only the areas that were painted by the drawing fluid would wash away, leaving a stencil around it. This process enabled the artist to incorporate their hand into the process, to stay true to their drawing.

A method that has increased in popularity over the past 70 years is the photo emulsion technique:

- The original image is created on a transparent overlay such as acetate or tracing paper. The image may be drawn or painted directly on the overlay, photocopied, or printed with an inkjet or laser printer, as long as the areas to be inked are opaque. A black-and-white positive may also be used (projected on to the screen). However, unlike traditional platemaking, these screens are normally exposed by using film positives.

- A screen must then be selected. There are several different mesh counts that can be used depending on the detail of the design being printed. Once a screen is selected, the screen must be coated with emulsion and let to dry in the dark. Once dry, the screen is ready to be burned/exposed.

- The overlay is placed over the emulsion-coated screen, and then exposed with a light source containing ultraviolet light in the 350-420 nanometer spectrum. The UV light passes through the clear areas and create a polymerization (hardening) of the emulsion.

- The screen is washed off thoroughly. The areas of emulsion that were not exposed to light dissolve and wash away, leaving a negative stencil of the image on the mesh.

Photographic screens can reproduce images with a high level of detail, and can be reused for tens of thousands of copies. The ease of producing transparent overlays from any black-and-white image makes this the most convenient method for artists who are not familiar with other printmaking techniques. Artists can obtain screens, frames, emulsion, and lights separately; there are also preassembled kits, which are especially popular for printing small items such as greeting cards.

Another advantage of screenprinting is that large quantities can be produced rapidly with new automatic presses, up to 1800 shirts in 1 hour.[18] The current speed loading record is 1805 shirts printed in one hour, documented on 18 February 2005. Maddie Sikorski of the New Buffalo Shirt Factory in Clarence, New York (USA) set this record at the Image Wear Expo in Orlando, Florida, USA, using a 12-colour M&R Formula Press and an M&R Passport Automatic Textile Unloader. The world speed record represents a speed that is over four times the typical average speed for manual loading of shirts for automated screen printing.[16]

Screenprinting materials

- Plastisol

- the most common ink used in commercial garment decoration. Good colour opacity onto dark garments and clear graphic detail with, as the name suggests, a more plasticized texture. This print can be made softer with special additives or heavier by adding extra layers of ink. Plastisol inks require heat (approx. 150°C (300°F) for many inks) to cure the print.

- Water-Based inks

- these penetrate the fabric more than the plastisol inks and create a much softer feel. Ideal for printing darker inks onto lighter coloured garments. Also useful for larger area prints where texture is important. Some inks require heat or an added catalyst to make the print permanent.

- PVC and Phthalate Free

- relatively new breed of ink and printing with the benefits of plastisol but without the two main toxic components - soft feeling print.

- Discharge inks

- used to print lighter colours onto dark background fabrics, they work by removing the dye in the garment – this means they leave a much softer texture. They are less graphic in nature than plastisol inks, and exact colours are difficult to control, but especially good for distressed prints and underbasing on dark garments that are to be printed with additional layers of plastisol.

- Flocking

- consists of a glue printed onto the fabric and then foil or flock (or other special effect) material is applied for a mirror finish or a velvet touch.

- Glitter/Shimmer

- metallic flakes are suspended in the ink base to create this sparkle effect. Usually available in gold or silver but can be mixed to make most colours.

- Metallic

- similar to glitter, but smaller particles suspended in the ink. A glue is printed onto the fabric, then nanoscale fibers applied on it.

- Expanding ink (puff)

- an additive to plastisol inks which raises the print off the garment, creating a 3D feel.

- Caviar beads

- again a glue is printed in the shape of the design, to which small plastic beads are then applied – works well with solid block areas creating an interesting tactile surface.

- Four colour process or the CMYK color model

- artwork is created and then separated into four colours (CMYK) which combine to create the full spectrum of colours needed for photographic prints. This means a large number of colours can be simulated using only 4 screens, reducing costs, time, and set-up. The inks are required to blend and are more translucent, meaning a compromise with vibrancy of colour.

- Gloss

- a clear base laid over previously printed inks to create a shiny finish.

- Nylobond

- a special ink additive for printing onto technical or waterproof fabrics.

- Mirrored silver

- Another solvent based ink, but you can almost see your face in it.

- Suede Ink

- Suede is a milky coloured additive that is added to plastisol. With suede additive you can make any colour of plastisol have a suede feel. It is actually a puff blowing agent that does not bubble as much as regular puff ink. The directions vary from manufacturer to manufacturer, but generally you can add up to 50% suede additive to your normal plastisol.

Versatility

Screenprinting is more versatile than traditional printing techniques. The surface does not have to be printed under pressure, unlike etching or lithography, and it does not have to be planar. Screenprinting inks can be used to work with a variety of materials, such as textiles, ceramics, wood, paper, glass, metal, and plastic. As a result, screenprinting is used in many different industries, including:

- Clothing

- Textile fabric

- Product labels

- Printed electronics, including circuit board printing

- Thick film technology

- Balloons

- Medical devices

- Snowboard graphics

- Signs and displays

Semiconducting material

In screen printing on wafer-based solar PV cells, the mesh and buses of silver are printed on the front; furthermore, the buses of silver are printed on the back. Subsequently, aluminum paste is dispensed over the whole surface of the back for passivation and surface reflection.[19] One of the parameters that can vary and can be controlled in screen printing is the thickness of the print. This makes it useful for some of the techniques of printing solar cells, electronics etc.

One of the most critical processes to maintain high yield. Solar wafers are becoming thinner and larger, so careful printing is required to maintain a lower breakage rate. On the other hand, high throughput at the printing stage improves the throughput of the whole cell production line.[19]

Garment decoration, modern application notes

Traditionally production garment decoration has relied on screen printing for printing designs on garments including t-shirts; recently, new methods and technologies have become available. Digital printing directly onto garments using modified consumer-quality, and task-specific designed inkjet printers. Screen printing, however, has remained an attractive, cost effective and high production-rate method of printing designs onto garments. Digital printing directly onto garments is referred to as DTG or DTS representing Direct To Garment or Direct To Shirt. DTG or DTS direct printing has advantages and disadvantages compared to screen printing. One noted advantage of DTG/DTS is number of visually perceived colors and the obvious photo-reproduction and photo-like print. DTG/DTS is often WYSIWYG an acronym for What You See Is What You Get, whereas screen printing often requires skilled artistic modification and then must be photo reproduced onto screens and printed. DTG/DTS has the advantage of quick one-off designs and small quantity orders where the screen printing process involves several independent time consuming steps. Screen printing is a production method and quickly overtakes DTG/DTS in cost per print as the higher the volume the lower cost per print becomes, screen printing also has the advantage of a large selection of different types of inks that are all considerably less expensive per garment than DTG/DTS inks.

Screen printing press

To efficiently print multiple copies of the screen design on garments, amateur and professional printers usually use a screen printing press. Many companies offer simple to sophisticated printing presses. Most of these presses are manual. A few that are industrial-grade-automatic printers require minimal manual labor and increase production significantly.

See also

- Dye

- Glass

- Ink jet

- Multi-layer

- Metal

- Plastic

- Printed electronics

- Printed T-shirt

- Roll-to-roll printing.

- Seriolithograph

- Textile printing

Notes

- ↑ http://www.sgia.org/

- ↑ http://www.merriam-webster.com/

- ↑ http://dictionary.reference.com

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/pss/4629553

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 http://www.screenweb.com/content/historys-influence-screen-printings-future

- ↑ http://www.artelino.com/articles/silkscreen-printing.asp

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 http://homepage.usask.ca/~nis715/scrnprnt.html

- ↑ http://www.freepatentsonline.com/2217718.html

- ↑ http://home.earthlink.net/~intothewoods/id28.html

- ↑ http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/serigraphy?r=14

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Printer's National Environmental Assistance Center Official website". http://www.pneac.org/printprocesses/screen/. Retrieved 2007-09-15.

- ↑ http://www.artelino.com/articles/andy_warhol.asp

- ↑ http://www.webexhibits.org/colourart/marilyns.html

- ↑ http://patft.uspto.gov/

- ↑ http://patft.uspto.gov/

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 http://www.sgia.org/surveys_and_statistics/

- ↑ Putting Your Reclaiming Tools to Work: Reclaiming Screens to Maximize Your Profits (Part 2)

- ↑ http://www.mrprint.com/EN/News.aspx?id=1129

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 http://www.omron-semi-pv.eu/en/wafer-based-pv/front-end/screen-printing.html

External links

- http://www.fespa.com/ - The Federation of European Screen Printers Associations

- http://www.sgia.org/ - SGIA - Specialty Graphic Imaging Association

- Understanding Silk Screening

- Silk Screening on Denim Fabric

- Champion Apparel - Tour of Screen Printing plant